The Impact of USMCA’s regional content rules on Canada’s auto industry

There is a narrative making the rounds in Ottawa that USMCA was a great deal negotiated during the first Trump administration that is only now being threatened by his amped up, anti-trade actions in his second term in office. To the contrary, Donald Trump has been remarkably consistent in his views on trade and both political parties in the US have shown their determination to back America First policies to Canada’s detriment. Moreover, history shows that the USMCA coincided with an accelerating decline of the Canadian auto industry — in part because of bad advice received by the Canadian government from parts of the Canadian auto sector. Now, history may be about to repeat itself.

Before going there, let’s deal with the issue of how the North American auto industry has performed recently.

We are now a quarter of the way into the current century, the start of which coincided with the termination of the Canada-US Auto Pact. In the year 2000, US vehicle sales clocked in at 17.4 million compared with just 15.85 million in 2024. That 9% drop in sales coincides with a period in which the population of the United States grew by about 22% to just over 340 million people. Meanwhile, automotive production in the US declined from 12.77 million to 10.6 million in 2023, a 17% drop even as international automakers continued to invest in new plants in the US.

Over the same period, vehicle production in Mexico climbed from 1.9 million vehicles in 2000 to 3.9 million in 2024.

What we have witnessed is what happens when free trade deals are structured around rules of origin that permit vehicles and the raw materials and parts they are made from to be sourced anywhere within the trade area. As Canada is coming to learn, content rules without the Auto Pact’s national production requirements mean that jobs and investment are drawn away to the country with the lowest wages (Mexico) or the country that offers access to the largest market (the US). US automakers have moved large parts of their production base to Mexico while international automakers have continued to invest in plants in the US (as well as Mexico) in order to get inside the US tariff wall and benefit from proximity to US consumers. So where does that leave us?

In Canada, production fell from 3 million vehicles in 2000 to half that number in 2023 and declined further in 2024. Meanwhile, population grew by roughly 30%. Sales in Canada also increased but at a slower pace, chalking up only 20% growth over the period.

While manufacturers continued to open new plants in the United States over the past 25 years, in Canada the last green field assembly plant was the Toyota Motor Manufacturing Canada Woodstock plant, which opened in 2008.

General Motors closed its plants in Oshawa, only to later reestablish a small truck assembly operation. GM’s CAMI facility in Ingersol lost Equinox production to a plant in Mexico and replaced it with Brightdrop electric vans that have struggled to find a market. Brightdrop notched a mere 1529 sales in the US last year and another 427 in Canada according to media reports. Not surprisingly, the plant has witnessed repeated shut downs and plant workers have joined others at GM’s propulsion plant in St Catherines on layoff.

Ford has shut down its remaining Canadian assembly operation in Oakville, first as a step toward retooling for the production of electric vehicles and, when that dream died, for full size pick up trucks. In the face of US tariffs the future of that plant remains in doubt.

The Stellantis Brampton plant was shut down for retooling to produce a new version of the Jeep Compass, including an electrified version. Originally expected to be back in operation this year, the restart has been paused as Stellantis considers its future plans. It is not surprising, therefore, that Canada has gone from enjoying a vehicle trade surplus to experiencing a trade deficit.

Honda and Toyota have been the bright spots of Canadian assembly operations, with the two Japanese makers accounting for roughly 950,000 of the 1.3 million vehicles produced in Canada last year.

US sales of new vehicles have seen two periods of decline and recovery over the past 25 years with a peak achieved around 2015. By comparison with their 2015 high, Ford sales were 20% lower in 2024 (roughly double the overall decline in the market) and Stellantis was down by an astonishing 42%. This sales retreat parallels the decision by US automakers to end car production and concentrate on large trucks and SUVs. One consequence of this shift is that transaction prices have risen rapidly across North America, contributing to an affordability crunch that may explain much of the automotive sales decline.

There is clearly a crisis in the North American auto industry, but imposing tariffs that will further drive up costs for consumers will just exacerbate the problem. But faced with the US move to raise the tariff wall, Canada must respond. Contrary to the Trump narrative that Canada has stolen US auto manufacturing, US exports to Canada have grown while Canadian production has fallen.

This brings me to two of the prevailing trade policy approaches being proposed by lobbyists in Ottawa. The first is that Canada should simply agree to further tightening content and other rules in order to restore some version of the pre-Trump 2.0 status quo under USMCA/CUSMA. The second is an approach that riffs off the recent US-UK agreement that saw the UK gain a reduced, 10% duty on a specified quantity of vehicles imported to the US on an annual basis.

Ever since Canada lost the production guarantees that were built into the Auto Pact, our industry has been in a long period of decline. Therefore, any inclination on the part of Canadian governments or industry to simply wish for a return to the pre-Trump 2.0 era is misplaced. The patient was already dying—just slowly.

It is also worth remembering that Canada’s competitive position was also under assault during the Biden administration as massive direct subsidies were provided to companies operating in the United States and efforts were made to establish discriminatory Buy America policies and consumer incentives. Playing nice with the US in the hope that it would avoid further repercussions was also not working. Canada and Mexico won a dispute over auto parts definitions that the US ignored and Canada decided not to press in order to prevent an early triggering of the USMCA review process. Cleary that didn’t gain us anything. Nor did the decision to apply a surtax to imports of Chinese EVs. Curiously, in that case Canada went further than the US and applied the surtax not just to EVs but also to hybrids.

Much worse is the suggestion that Canada should agree to a UK-style tariff agreement so long as the US allows importers to deduct the value of US content (resulting in perhaps a 5% applied rate of duty). Such a proposal would lock in a persistent cost disadvantage for Canadian auto plants that might be equivalent to $1,500 per vehicle and, in the worst case, would also lead to Canada dropping its surtax on US vehicles. Some industry players have suggested throwing in a deal to terminate the Canadian federal ZEV mandate as a further sweetener for the Trump White House. The same US auto makers that, like the Cheshire Cat, have been staging a disappearing act from Canadian manufacturing might welcome such a deal.

Canada should push back. Agreeing to lock in a permanent price disadvantage for Canadian built vehicles made with Canadian parts and materials would signal the end of the Canadian industry. In addition, while Canada can choose to agree to align regulatory standards with the US, it should not yield its sovereign right to set its own regulations.

This debate about the future of the Canadian auto industry should be top of mind for all Canadians. Whether and how Canada commits to maintaining its economic and political independence in this case will establish an important precedent for other sectors and other policy matters. It is important to understand that there is no preordained or inevitable outcome in that regard.

We have heard President Trump repeatedly say that the US does not need Canadian cars. That’s true. There is a world of choice and no shortage of auto plants across the United States and around the world that are prepared to meet US demand. What the US does need, on the other hand, is our market.

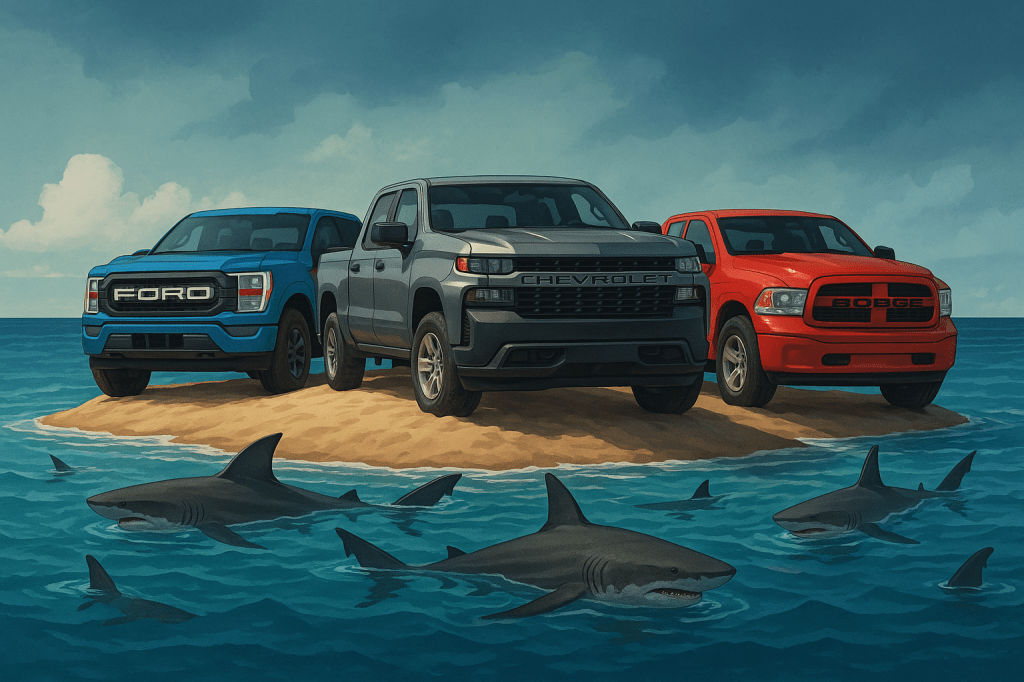

The US has precisely one good market for the pickup trucks and other large vehicles that its plants specialize. That market is Canada. Unlike the US, the Canadian sales continue to grow. That’s important.

US automakers have significantly reduced their global footprint over the past quarter century, having retreated from Europe and Australia and seen their share of the Chinese market plummet. GM, Ford and now Tesla are standing on a shrinking patch of high ground, watching the water rising around them. The US makers will be stronger if they retain access to a closely aligned Canadian market. On the other hand, contrary to the current talk track in Washington, the loss of that market could prove to be the last straw for certain manufacturers.

Consider, for example, that Ford’s US sales were 20% lower in 2024 than they were at the turn of the century. As of last year, the Ford F-150 was no longer the top selling vehicle in the United States—but it retains that leadership in Canada. Auto plants need to operate at or close to capacity in order to be profitable. The loss of Canadian sales could easily mean the difference between the success or failure of one or more US plants. Similarly, Tesla is currently dead in the water in Canada if surtaxes are applied to all of their imports and any consumer incentives offered in Canada no longer apply because of the price effect of tariffs on Tesla vehicles.

For Canada to negotiate a short term reprieve while agreeing to a lingering death is not a good option for anyone. The moment we agree to give up on one sector, all others are at risk. At least in automotive, Canada has leverage today and we need to use it, not just hand it away.

For that reason, I have advocated for a return to the managed trade principles of the Auto Pact. Tying the right of duty free imports to a production mandate is the very definition of the reciprocity that Washington has been calling for. Applied in both directions, trade would balance and the opportunity for growth would come from manufacturers in both countries investing to improve productivity and bring compelling new products to market. To me, that seems a better outcome than allowing the continuing drift of industrial jobs and investment from Canada.

Taking a bold stance in this instance will mean that the Canadian government has to overlook the advice it is receiving from certain parts of the industry. But that is the job of governing. Doing the right thing, not just what a certain narrow interest has advocated for, is what we elect governments to do. And in the absence of evidence to the contrary, I believe that the Carney government has both the inclination and the opportunity to protect Canada’s future.

Leave a comment