Everything old is new again.

While using the language of trade liberalization and market access, free trade deals in North America have increasingly become platforms for trade manipulation and have left the Canadian auto industry at a competitive disadvantage.

In the late 1980s, senior policy makers worried about Canada’s low productivity and decreasing competitiveness on the global stage. Their response was the Canada-United States Free Trade Agreement (CUSFTA), a form of shock treatment that eliminated protective tariffs with our largest trading partner. For the auto industry, however, CUSFTA was a step backwards.

CUSFTA represented the first large scale introduction of rules of origin, the definitions and practices that are the pre-conditions for the duty free flow of goods between free trade partners. Central among those were the automotive rules of origin that have evolved over subsequent free trade agreements (i.e., NAFTA, CUSMCA ).

Several general design features have remained across those deals including an overall emphasis on the use of raw materials and inputs originating from the parties to the agreement; increasingly detailed content and manufacturing requirements; and, most importantly, the complete absence of any domestic assembly requirements. Under our agreements with the United States “originating” duty free automobiles may be produced anywhere on the North American continent.

The pernicious impacts of having no Canadian assembly requirements including the inevitable migration of automotive assembly operations to lower cost jurisdictions or the draw to locate closest to the largest market have resulted in trade agreements that are becoming increasingly hostile to trade at any level.

In the auto industry it is the auto makers or OEMs who are the apex predators and when they go extinct, so does the entire food chain. The tariffs that Donald Trump has mused about would simply hasten an outcome that Canada had already baked into its trade deals.

There is an alternative. The germ of that idea is found in the way we used to conduct trade. I have come to believe that it is time to reconnect with our history.

There is a common narrative, put forward by representatives of the auto parts sector, the major automotive union and certain politicians, that the USMCA (CUSMA) was a great victory for Canada and for the principles of free trade. In fact, nothing could be further from the truth.

Through most of Canadian history, free trade with the United States was opposed by at least one of the dominant, federal political parties. Canada needed tariff protection, it was argued, to prevent our industries from being overrun by their US competitors. The early auto industry grew up behind a tariff wall and people only began to rethink that strategy as the industry limped into the 1960s.

With a small domestic market that nonetheless demanded consumer choice, automakers in Canada were not able gain economies of scale while producing only for Canada. Exports to trading partners where Commonwealth tariff preferences applied were impractical. As a result, Canada and the US negotiated the Auto Pact, which allowed for the integration and rationalization of production on a North American scale and for free trade in automotive products so long as certain production minimums were achieved in both jurisdictions. In other words, the two countries agreed to investment requirements as the key to unlocking the benefits of an open market.

The Auto Pact did what it set out to do. The industry realigned, two-way trade expanded and vehicle prices moderated as consumer demand grew. Contrary to today’s conventional wisdom, the Auto Pact was not a sectoral free trade deal, it was a managed trade pact. Concessions were given based on certain performance guarantees and it was a closed club. No new companies could join except through acquisition of an existing member.

Unfortunately, the deal was asymmetric. Canada allowed manufacturers to obtain benefits for imports from third countries, while US importers only gained access to duty free imports from Canada. Canada also used other trade and investment tools to attract new entrants to the industry, although the benefits they received from manufacturing in Canada were set at a second, lower tier. As a result of a wave of company consolidations in the 1990s, Canadian Auto Pact participants were able to import vehicles from affiliated companies anywhere in the world based on their Canadian manufacturing footprint.

In other words, Canada undermined the domestic manufacturing requirement that was at the heart of the Auto Pact by introducing a loophole that permitted duty free goods from brands with no domestic manufacturing footprint. This lopsided deal ended with Canada being hauled before the WTO and declared in contravention of global trade rules. It was not the performance guarantees of the Auto Pact that led to its demise but Canada’s decision to bake in exceptions to those rules for some but not all. Although grandfathered into the North American Free Trade Agreement the Auto Pact died as a result of the the WTO ruling and a very different set of trade rules and principles governed automotive trade going forward.

The Auto Pact was proof positive that a managed trade deal could work and provide mutual benefits to the contracting parties, but it needed complementary rules in each jurisdiction and active, continued management by the parties. By the mid-1980s, federal politicians looking to restructure the Canadian economy looked at the precedent of the Auto Pact, made the mistake of thinking it was a actually a sectoral free trade deal, and thought that a sweeping free trade pact could provide similar broad benefits for the Canadian economy as a whole.

They missed the point. The fact that the rules around automotive trade were fundamentally altered in the Canada-US FTA and subsequent trade deals should have been the first clue that the principles of the Auto Pact were being set aside in this new trade environment.

The Auto Pact was all about “tariff shift”. Companies gained benefits from transforming parts and materials from one tariff heading to vehicles in another tariff heading. In other words, benefits flowed from simple assembly — using inputs to make finished goods. In the subsequent FTAs, the rules started to be quite explicit about content requirements. Goods not only had to be products of one or more of the contracting parties but a specified percentage or explicitly defined set of inputs had to be incorporated into the finished product for that automobile to qualify for free trade benefits. In effect, the vehicle came to be defined by its supply chain. The FTAs represented a victory for sectors like steel and aluminum and parts makers over the finished goods producers. While politically attractive, that was a fundamental error on the part of US and Canadian trade negotiators and politicians.

The genius of the Auto Pact was that it required local assembly in order for manufacturers to avoid having to pay the relatively high external duties on imported vehicles. Access to each market required local production.

Content based rules of origin, on the other hand, tie market access to the use of materials sourced from suppliers within the trade area. Trade negotiators, under pressure from upstream industries have made those content rules more stringent with each new FTA, increasing the complexity and cost of qualifying vehicles for free trade. The problem is that, if the cost of complying with those rules is greater than the value of the external duty rate on finished vehicles, companies will simply ignore the FTA and claim the Most Favoured Nation rates of duty (2.5% for most vehicle imports to the United States, excluding trucks, and 6.1% for all vehicles in Canada).

Final assembly operations represent the top of the food chain. If those manufacturing operations prosper in a given jurisdiction, they will maintain healthy supply chains, particularly in industries such as automotive where the inputs are heavy and are required to be supplied on a just in time basis. Suppliers will locate in proximity to auto plants to reduce logistics costs and increase delivery certainty. It is their inherent advantage over foreign producers. Automakers don’t need to be told to source locally. It is a self-evident imperative. So the trick is to anchor assembly plants in your jurisdiction and everything else will follow.

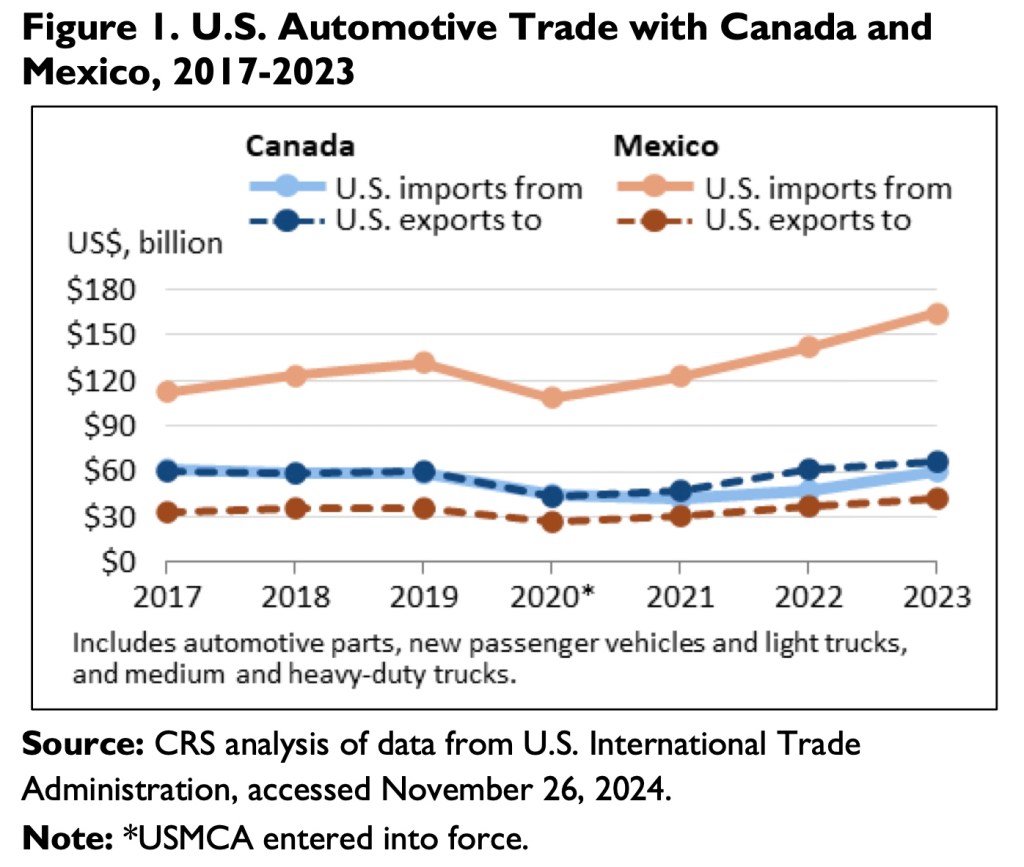

In the absence of domestic assembly requirements plants can be relocated anywhere within the trading area where costs can be optimized. In the context of North America, that not surprisingly means that companies are forced to at least consider production in Mexico with its lower labour costs and less evolved regulatory standards. Nobody should be surprised that Mexico has dramatically increased its share of North American trade post USMCA. The following chart produced by the Congressional Research Service in the United States highlights that shift.

Equally telling is the fact that the share of Mexican imports to the US that are claiming the MFN, not FTA, rate of duty has climbed from 4% in 2019 to 16% in 2023. The USMCA rules appear to be pushing production to Mexico without the need for local sourcing of parts and materials. That is a troubling outcome in a period of rapid technological change.

The emphasis on content rules of origin in trade deals like the USMCA means that a specified set of manufacturing processes has to occur within the region in order to qualify the final vehicle for free trade benefits. Imagine then that certain emerging technologies are either not produced in the region or are produced on a limited scale and therefore not broadly available to the vehicle assemblers from North American suppliers. Battery technology, chips, and technical grades of steel and aluminum all spring to mind.

The nature of trade is that, assembly plants need to locate in areas that give them access to the largest possible market, with the hope of expanding as supply availability improves. This implies that manufacturers should site assembly plants in Mexico to obtain lower costs or in the United States in order to gain duty free access to American consumers and/or the investment incentives and consumer rebates offered by the US.

By insisting on highly detailed rules of origin with extremely high domestic content requirements, trade negotiators, unions and lobbyists have counted Canada out of the competition. The advocates for this approach will point to various announcements concerning potential battery plants in Canada as justification for their approach. But it is a costly approach. It forces Canadian governments to have to match the incentives provided in the US or lose investment.

Those subsidies were offered but many of the resulting investments been delayed or cancelled in the face of political and market uncertainty. They were also generally company-specific. Their inherently restrictive nature ensured that there would be limits placed on vehicle assembly in Canada.

In a nutshell, Canada managed to negotiate itself into a declining manufacturing base as it either lost investment and jobs to Mexico or restricted itself to only making those vehicles for which a domestic supply base exists or could be competitively established. In the face of massive US government incentives, Canada’s opportunity to build out supply chains for the first wave of connected and electrified vehicles was always going to be limited.

Economists tend to look at deals like this and say that one has to consider the net benefits of trade. Do trade volumes increase after a deal? Does employment rise? What about GDP?

Clearly, two-way trade between Canada and the US did grow following the Canada-US FTA. At the same time, the Canadian government’s own studies showed that manufacturing employment declined and service sector employment increased. Canadian GDP has lagged.

By way of example, at the time of the original FTA, the apparel industry was a top ten employer in Canada, accounting for roughly 100,000 jobs. Today it has been decimated as production has fled to Mexico, China or other production centres. The FTA introduced auto industry style rules of origin (based on transformation of locally produced textile inputs) to the apparel sector. It diminished the value of the labour inherent to manufacturing clothing in favour of producing fibres (wool, cotton, synthetics). By agreeing to those rules, Canada allowed US brands to dominate the market through the use of US textiles to make commodity apparel. Whether through outward processing in the early stages of this trade realignment or outright repositioning of garment assembly in Mexico in later deals, Canadian manufacturing jobs were traded away as tariffs declined through various bilateral trade pacts and quotas were eliminated from the global trade in finished apparel.

But no problem. Overall employment grew in Canada over subsequent decades. What is overlooked is that many of the new jobs are precarious, part time, and lacking the benefits that manufacturing jobs yield. It is shocking to see that the City of Toronto considering capping ride-share licences for drivers with companies like Uber and Lyft at the December 1, 2024 number of 80,429.

CBC News reported that it is estimated that 14 out of every 100 vehicles in downtown Toronto are being employed in ride-hailing. Consider that this does not account for taxis, other courier services or commercial vehicles and you begin to understand the scale of the gig economy in this one sector of the economy. It seems the employment effect of the garment industry and others may have been largely replaced by Uber and Lyft. They are just the tip of the iceberg. But those gig jobs come with few benefits, lower net income and fewer women employed.

Perhaps the loss of apparel jobs was inevitable. The auto industry with its greater capital intensiveness and highly sophisticated production systems must be different, one might say. The numbers appear to paint a different picture.

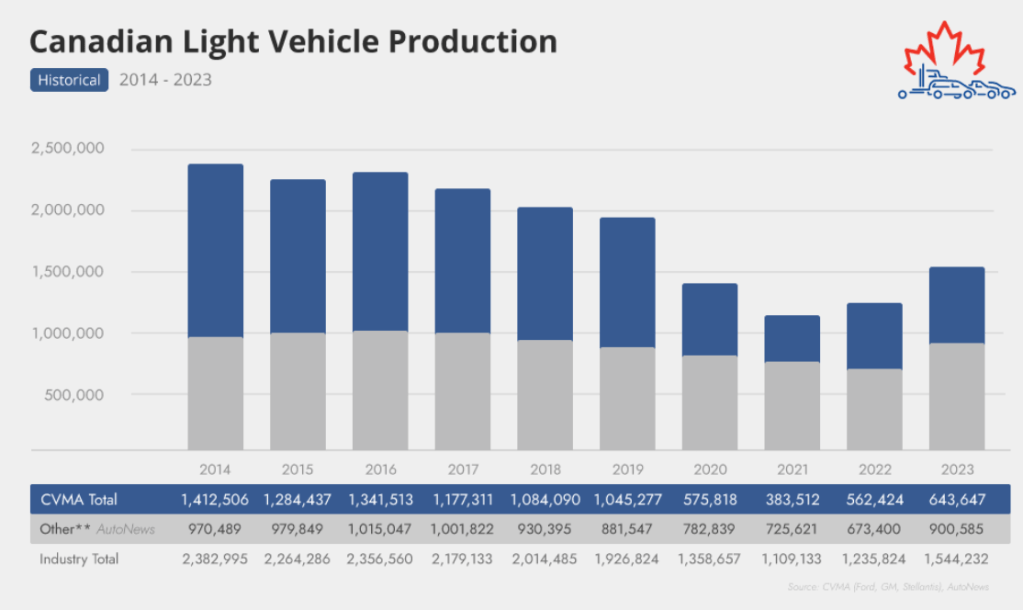

What happened to automotive manufacturing in the modern trade era? The following chart is taken from the Canadian Vehicle Manufacturers Association website (the CVMA is the Canadian trade association representing Ford, GM and Stellantis).

Since 2020, GM has moved Equinox production out of Canada in favour of small volume production of BrightDrop vans and Ford has halted production in Oakville that will ultimately be partially replaced by full-size pickup assembly in 2026 at a net loss of jobs. The production halts and subsequent downsizing of operations have also impacted jobs at various supplier plants in Canada. All of this would be OK (not accounting for the human impact of dislocation as a result of restructuring) if the predicted boom in EV manufacturing and the EV supply chain were to happen. But that seems increasingly unlikely in the near term.

The point then is this: It is time to rethink our approach to trade. The Trump Administration may be doing us a favour by insisting on renegotiating the trade deal with Canada and Mexico. American companies no longer create an automotive trade surplus for Canada. For the first three quarters of 2024, for example, Ford and GM produced 167,535 vehicles in Canada. They sold over 432,000 in that same period. To paraphrase, why are we subsidizing the United States? A managed trade deal could bring the numbers back into balance and, using a simpler tariff shift or value-added test, could reduce the cost and complexity of administering trade for both industry and government. If manufacturing scales up to balance with sales, the supply chain should witness growth as well. The rising tide will lift all boats.

While relatively simple, the trade mechanics required to achieve this outcome are still too detailed for a short article but they are based on precedent and they are eminently doable. What they require above all is an ability to see a different path and a willingness to abandon the status quo.

That status quo has not served us well and, in the face of rising trade protectionism in the US, it is time to embrace change. Will the Canadian trade establishment rise to the occasion offered by a USMCA review?

.

Leave a comment